Frontroom Overview

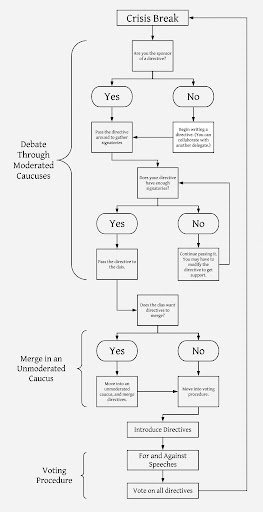

In crisis the frontroom is driven by what is referred to as the crisis cycle. Over the course of a crisis committee, you will go through dozens of “Crisis Cycles.” The frequency of these cycles is what makes the committee fast paced and engaging. Each Crisis Cycle will have a different focus, but has the same format of Crisis Break, then Debate, then Directives.

Crisis breaks, also known as crisis updates, are the main way that the committee learns about the state of the world in a crisis committee. The Crisis Director and Assistant Chairs will enter the room and inform the committee about events that have occurred outside the committee doors. These will often be presented as short skits, with the ACs acting as relevant characters (protestors, activists, military personnel, economists, ambassadors, etc).

The primary purpose of crisis breaks is to present new problems that the committee will have to solve. For example, if the committee was President Obama’s Cabinet, a possible crisis break would be North Korea testing a new nuclear weapon and threatening to launch it at the US. Committee would then have to decide how to respond to this threat and keep Americans safe. Your crisis staffers will sometimes suggest a few possible solutions to the crisis as part of the break, but it will be the committee’s job to create and implement a solution. In the example of the North Korean threat, your staffers might outline a diplomatic option (negotiating with North Korea) an economic option (imposing further sanctions) or a military option (launching an attack on North Korean missile sites). The committee would debate the feasibility of these options along with their benefits and consequences.

Near the end of a crisis break, delegates usually have the chance to ask questions about the information they just heard. Don’t be afraid to ask questions! This is a great opportunity to clarify anything from the update that might have confused you. When asking questions try not to focus on numbers, ACs are trained not to give specific answers, instead of asking “how many protesters are there?” ask “are the protesters' views shared by the people?”, or “do the protesters pose an immediate threat to our power?” A few common topics for questions are:

Resources – What resources does the committee have available to solve the crisis? This can include money, military equipment, personnel, or intelligence. For example, in the North Korean crisis, it might be helpful to ask about what intelligence the CIA has on North Korea’s missile sites.

Public awareness – Who else knows the information that the committee just heard? This is especially important in political committees, where scandals often come to light, and the committee might want to prevent the public from finding out.

External responses – How have entities outside of committee responded to this crisis? In a cabinet committee, it might help to ask how neighboring countries have reacted to an international crisis. It might also help to ask about potential alliances that the committee could make to solve the crisis.

Debate

Just like in General Assembly committees, most of the debate in crisis committees occurs in moderated caucuses. After a crisis break, the committee will usually enter a moderated caucus to propose and debate possible solutions to the crisis. When the committee has several options of responding to the crisis, a moderated caucus lets delegates share opinions about which option is best and how the committee should implement it. Crisis speeches are generally more specific and direct than GA speeches, with details about the solutions that are being proposed. You can also use speeches to support or critique solutions that other delegates have proposed.

Since crisis committees are relatively small, you’ll have the chance to speak much more often than in a General Assembly. Try to speak as much as you can! Speaking is the best way for other people to hear about your ideas, and your speeches can often convince people to collaborate with you. Since crisis speeches are usually impromptu and less formal than GA speeches, there’s no pressure to make a “perfect” speech.

Directives

One proposed solution to a crisis break is written into a document called a directive. Directives are handwritten and relatively short. A directive is typically about one to four pages long, but the dais will specify their expectations. Directives are written as a series of actions that the committee will take to respond to the crisis break. These actions should be specific and direct, outlining exactly what resources the committee will use, and how these resources will be deployed. Below, you’ll see an example of a directive with the typical format and level of detail. This directive is responding to the North Korean missile threat that was mentioned in the Crisis Breaks section.

Delegates should take notes during the crisis break so that they can start writing directives once the crisis break has finished. While delegates are speaking during moderated caucuses, directives are passed around the committee so that people can read them and sign on as signatories. Once directives have enough signatories, they are passed up to the dais. If the dais sees that there are many directives, or that most directives have similar directives, they will suggest that delegates merge directives. Delegates can motion for an unmoderated caucus, and after this is granted, directives can be merged to fill any quotas set by the dais (in terms of signatories, number of directives, and page numbers per directive).

Unmoderated caucuses are also useful for working as a group to come up with a solution that has enough votes to pass. Delegates can then motion to introduce directives, where the chair will read the directives out to the committee.

After directives have been introduced, delegates can motion to vote on directives, along with the number of speeches in “for and against'', or have a moderated caucus or two debating the merits of the competing directives. The first option is the most common but if there are multiple large blocs each with their own directive, it may be productive to debate more. This further debate also gives delegates a chance to write amendments that can bring more votes over to their side. Amendments are usually fairly short and include a clause or two that slightly changes, or expands an existing directive. There are two types of amendments, “friendly” and “unfriendly”. For an amendment to be a “friendly” amendment all of the original directive’s sponsors must sign on to it and it is automatically added to the directive when voting, if the directive is passed so is the amendment. If not all of the sponsors of the original directive agree to an amendment it is “unfriendly” and it must be voted on separately from the directive. Unfriendly amendments however are not stand alone directives and if the directive it is attached to does not pass then the amendment automatically will not either.

In voting procedure directives can be voted on immediately, but a common practice is to first hear speeches for and against the directives. “One for one against” means that one person will speak in favor of passing the directive, and one person will speak against passing it. Similarly, “two for two against” means that two people will speak in favor, and two people will speak against, with the for and against speeches alternating. Two for two against is the most common option, and often your chair will request that you stick to this, but if there is a time crunch they may move you straight to voting. After all for and against speeches, directives are then voted on. Delegates can vote for, against, or abstain. A directive passes if it receives a simple majority of votes.

Once a directive has been passed, the committee has officially taken the actions outlined in it. If two directives pass that take contradictory actions, the directive that was passed later takes precedence. It is assumed that the official actions of the committee will be from the later directive, rather than the previous one. Passed directives are sent to the crisis room, where your crisis staff will decide what impact committee’s actions had on the simulated world. They will then create a new crisis break based on the directive. Your CD and ACs will come back into the committee room to inform the committee of the impact their directive had on the crisis situation, and will present the new crisis break. Depending on how effective they thought your solution was, this crisis break might be a completely new problem to solve, or build upon the previous break. Delegates will then discuss solutions to this new problem, restarting the cycle of committee.