Crisis Committees

What is a Crisis Committee?A crisis committee is a decision making body that has more power than a traditional committee. Whilst General Assemblies recommend and build consensus, focusing on creating and refining frameworks for the nations party to align their actions, crisis committees produce action. This means that the body has power unto itself that does not need to be granted by the obedience of its members. Groups that look like this include a cabinet, a royal court, a board of directors of a company, a rebel group, or really any small group which possesses political power. Crisis is also more dynamic and fast-paced than traditional committees, so each delegate is incredibly influential. In your preparation, it is helpful to understand the committee’s basic history and scope of power, as found in the background guide. The Structure of Committee

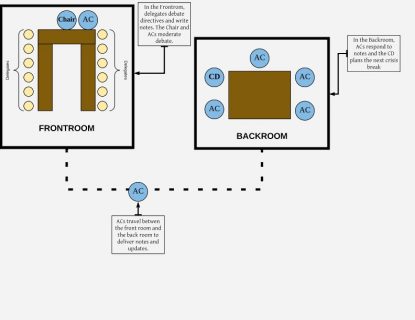

Continuous Crisis committees all have a “Frontroom” and a “Backroom.” The Frontroom is the committee room itself. Instead of writing resolutions, the Frontroom will pass  |

The Background Guide

As you read the background guide, think of the historical context. The MUNUC staff who run the committee are the same people who write the background guide. So, the background guide is full of hints as to what the topics of debate will be. As you read the background guide, think of key themes that have appeared in the history leading up to committee, along with “current” issues at hand. For example, if a committee is titled “USA in 1987,” and the background guide is filled with details about the Cold War, the committee will certainly involve events surrounding the collapse of the USSR: the fall of the Berlin Wall, economic relations with reforming countries, denuclearization, etc. Knowing the focus of the committee will help you respond quickly to crisis breaks and can help you write more topical notes.

As you read, be sure to take notes on what caused the current state of the committee. Other things to note are key personnages that might make an appearance either in updates or as the motivator behind challenges the committee will have to face. This could include politicians, countries, rebel groups, companies, and any other key actors.

Additionally, the background guide will include biographies or “bios,” which define each delegate’s character. From the bio, you can clearly see the powers of your role and also any resources you already have, which are called “portfolio powers.” The bio might also hold some hints or tips for your character, and is certainly not exhaustive. With some imagination and independent research, you also assume your character’s morals, political alignment, connections, and any other resources that you would have at the start of committee.

The chair and crisis director of the committee welcome these assumptions so long as these are logical and relatively accurate. Bios are meant to be a starting point. You are encouraged to define your character as you see fit. If you ever worry that your ideas about your character are too extreme, then ask the crisis director for further direction.

The conference weekend begins with Crisis Breaks heavily linked to the background guide. However, as the committee evolves, individual delegates can affect the committee by exercising their portfolio powers, and causing new Crisis Breaks. Each delegate writes crisis notes to build up and use resources to promote a personal agenda. So, while the background guide is the basis of delegate powers and the committee’s goals, history will quickly veer in new directions.

The Crisis Cycle

Over the course of a crisis committee, you will go through dozens of “Crisis Cycles.” The frequency of these cycles is what makes the committee fast paced and engaging. Each Crisis Cycle will have a different focus, but has the same format of Crisis Break, then Debate, then Directives.

Crisis Breaks

Crisis breaks, also known as crisis updates, are the main way that the committee learns about the state of the world in a crisis committee. The Crisis Director and Assistant Chairs will enter the room and inform the committee about events that have occurred outside the committee doors. These will often be presented as short skits, with the ACs acting as relevant characters (protestors, activists, military personnel, economists, ambassadors, etc).

The primary purpose of crisis breaks is to present new problems that the committee will have to solve. For example, if the committee was President Obama’s Cabinet, a possible crisis break would be North Korea testing a new nuclear weapon and threatening to launch it at the US. Committee would then have to decide how to respond to this threat and keep Americans safe. Your crisis staffers will sometimes suggest a few possible solutions to the crisis as part of the break, but it will be the committee’s job to create and implement a solution. In the example of the North Korean threat, your staffers might outline a diplomatic option (negotiating with North Korea) an economic option (imposing further sanctions) or a military option (launching an attack on North Korean missile sites). The committee would debate the feasibility of these options along with their benefits and consequences.

Near the end of a crisis break, delegates usually have the chance to ask questions about the information they just heard. Don’t be afraid to ask questions! This is a great opportunity to clarify anything from the update that might have confused you. A few common topics for questions are:

Debate

Just like in General Assembly committees, most of the debate in crisis committees occurs in moderated caucuses. After a crisis break, the committee will usually enter a moderated caucus to propose and debate possible solutions to the crisis. When the committee has several options of responding to the crisis, a moderated caucus lets delegates share opinions about which option is best and how the committee should implement it. Crisis speeches are generally more specific and direct than GA speeches, with details about the solutions that are being proposed. You can also use speeches to support or critique solutions that other delegates have proposed.

Since crisis committees are relatively small, you’ll have the chance to speak much more often than in a General Assembly. Try to speak as much as you can! Speaking is the best way for other people to hear about your ideas, and your speeches can often convince people to collaborate with you. Since crisis speeches are usually impromptu and less formal than GA speeches, there’s no pressure to make a “perfect” speech.

Directives

One proposed solution to a crisis break is written into a document called a directive. Directives are handwritten and relatively short. A directive is typically about one to four pages long, but the dais will specify their expectations. Directives are a series of actions that the committee will take to respond to the crisis break. These actions should be specific and direct, outlining exactly what resources the committee will use, and how these resources will be

deployed. Below, you’ll see an example of a directive with the typical format and level of detail. This directive is responding to the North Korean missile threat that was mentioned in the Crisis Breaks section.

Sample Directive

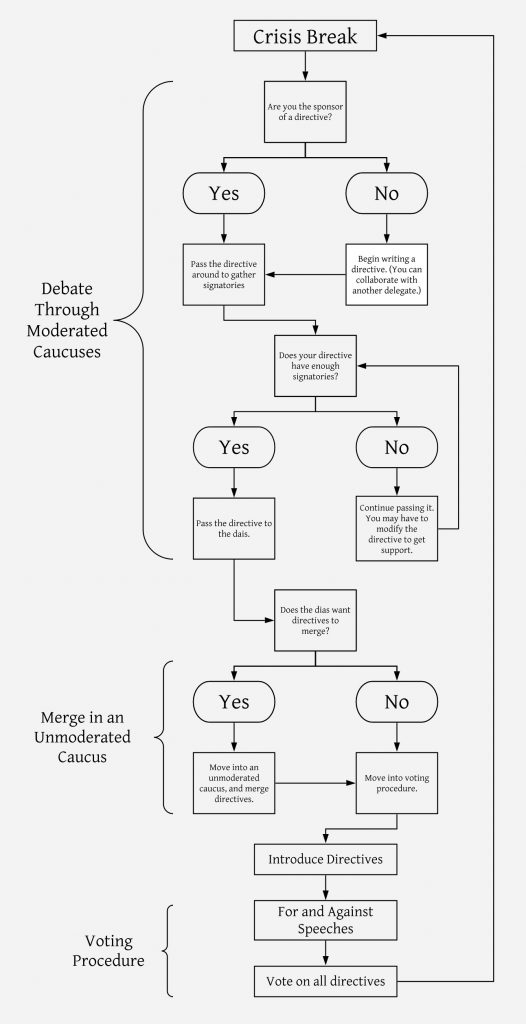

Delegates should take notes during the crisis break so that they can start writing directives once the crisis break has finished. While delegates are speaking during moderated caucuses, directives are passed around the committee so that people can read them and sign on as signatories. Once directives have enough signatories, they are passed up to the dais. If the dais sees that there are many directives, or that most directives have similar directives, they will suggest that delegates merge directives. Delegates can motion for an unmoderated caucus, and after this is granted, directives can be merged to fill any quotas set by the dais (in terms of signatories, number of directives, and page numbers per directive). Delegates can then motion to introduce directives, where the chair will read the directives out to the committee.

After directives have been introduced, delegates can motion to vote on directives, along with the number of speeches in “for and against.” Directives can be voted on immediately, but a common practice is to first hear speeches for and against the directives. “One for one against” means that one person will speak in favor of passing the directive, and one person will speak against passing it. Similarly, “two for two against” means that two people will speak in favor, and two people will speak against, with the for and against speeches alternating. After all for and against speeches, directives are then voted on. Delegates can vote for, against, or abstain. A directive passes if it receives a simple majority of votes.

Once a directive has been passed, the committee has officially taken the actions outlined in it. If two directives pass that take contradictory actions, the directive that was passed later takes precedence. It is assumed that the official actions of the committee will be from the later directive, rather than the previous one. Passed directives are sent to the crisis room, where your crisis staff will decide what impact committee’s actions had on the simulated world. They will then create a new crisis break based on the directive. Your CD and ACs will come back into the committee room to inform the committee of the impact their directive had on the crisis situation, and will present the new crisis break, giving the committee a new problem to solve. Delegates will then discuss solutions to this new problem, restarting the cycle of committee.

Important Motions to know for Continuous Crisis

Moderated Caucus: The chair will call on delegates to speak one-by-one. Delegates will raise their placards if they want to speak. Moderated caucuses have a set topic, speaking time (usually 30-60 seconds), and number of speakers

Example: “Motion for a 9 minute moderated caucus with a 45 second speaking time on the topic of international alliances.”

Round Robin: Going around the room, every delegate in the committee makes a speech. Round robins also have a set topic and speaking time.

Example: “Motion for a round robin with a 30 second speaking time on the topic of military vs. diplomatic options.”

Unmoderated Caucus: Delegates will be able to move freely around the room and talk to/work with other people. Unmoderated caucuses have a set time limit (usually 5-15 minutes), but you do not specify a topic.

Example: “Motion for a 10 minute unmoderated caucus.”

Extension: Extends the current moderated/unmoderated caucus by a certain amount of time.

Example: “Motion to extend the current moderated caucus by 6 minutes.”

Introduce Directives: The chair will read out loud all of the directives that have been passed up to the dias. Directives need to be introduced before they can be voted on.

Example: “Motion to introduce all directives on the table.”

Voting Procedure (For/Against): For every directive that has been introduced, 1-2 delegates will make a speech in favor of passing a directive,

and 1-2 delegates will make a speech against it. The committee will then vote on the directives, with a simple majority being required to pass. You should specify how many speakers the for/against will have and the speaking time.

Example: “Motion to move into voting procedure with 2 for, 2 against, 45 second speaking time.”

Voting Procedure (Direct): The committee will vote on the directives immediately without any speeches for/against.

Example: “Motion to move directly into voting procedure on all directives.”

Note Writing

Notes are the main component which separate traditional committees from those with crisis elements. If your committee has crisis elements, you receive one or two notepads at the start of your first session. You use these to write plans, actions, questions, plots, etc. Think of this as writing to your private secretary who is able to act on your behalf outside the committee.

The dais of your committee will periodically collect these notepads and respond to your note. If you use your notes effectively, you’ll be able to promote your private interests, build alliances, use portfolio powers, and obtain new resources and powers.

Ultimately, notes build your importance and power in committee. With a series of well written notes, you can take the spotlight of the committee. The next “crisis break” can be about you and your plans, which is a good goal to have. When your notes are causing crisis breaks, you become more influential in the decisions of the committee.

It’s also important to keep in mind that over the course of a weekend, you will be writing dozens of notes. So, your response might ask you a lot of questions about your plans, such as “How should I pay for this?” or “What do you want to do next?” This is normal, and you are expected to answer all these questions in order to make your plans happen.

The Three R’s

When writing a note, it is important to keep the information simple. One way to make your notes clear and concise is to describe the Three R’s: Resources, Request, Reasoning.

Examples of Resources

“I would like to use my army of socialist university students.”

“I was thinking I should sell some of the bananas on my banana farm.”

“Remember my friend James, the husband of the president? We met in college.”

Examples of Requests

“Move the army of socialist university students, along with their supplies, to the capital of France.”

“Sell these bananas and begin to buy catapults, trebuchets, and slingshots.”

“Ask my friend James if he wants to be the governor of Florida — I believe this role would suit him well.”

Examples of Reasonings

“Once the army of socialist university students is in the capital, we can begin to protest the horrid capitalist policies of the government. Here, we can demonstrate, and soon turn this tyranny into a utopia!”

“After purchasing this medieval weaponry, we can set up a renaissance fair in New Jersey, where we will begin convincing New Jerseyians of the inevitable Dark Age Revolution (DAR).”

“If James wants to be the governor of Florida, I will endorse him in the primary elections, and will divert government funds to his campaign. With him as governor, we are one step closer to the independent Dictatorship of Florida.”

Now, let’s think about what happens when you put Resources, Request, and Reasonings together. You establish what power you already have, you make a simple request, and then you justify this request. When using the Three R’s, you present your note in an easily understandable manner, which is more appealing to the dais. You are certainly welcome to add more details in your note, but this is a perfect foundation to keep in mind. Here are some examples of what the note looks like when you put the Three R’s together.

Example 1

Dear Secretary,

I would like to use my army of socialist university students. Move the army of socialist university students, along with their supplies, to the capital of France. Once the army of socialist university students is in the capital, we can begin to protest the horrid capitalist policies of the government. Here, we can demonstrate, and soon turn this tyranny into a utopia!

Best,

Jean Valjean

Example 2

Hello Farmer Frank,

I was thinking I should sell some of the bananas on my banana farm. Sell these bananas and begin to buy catapults, trebuchets, and slingshots. After purchasing this medieval weaponry, we can set up a renaissance fair in New Jersey, where we will begin convincing New Jerseyians of the inevitable Dark Age Revolution (DAR).

Sincerely,

Dan the Banana Man

Example 3

Dearest husband,

Remember my friend James, the husband of the president? We met in college. Ask him if he wants to be the governor of Florida — I believe this role would suit him well. If James wants to be the governor of Florida, I will endorse him in the primary elections, and will divert government funds to his campaign. With him as governor, we are one step closer to the independent Dictatorship of Florida.

Love,

Charles Orlando

Extra Details

Data Visualization

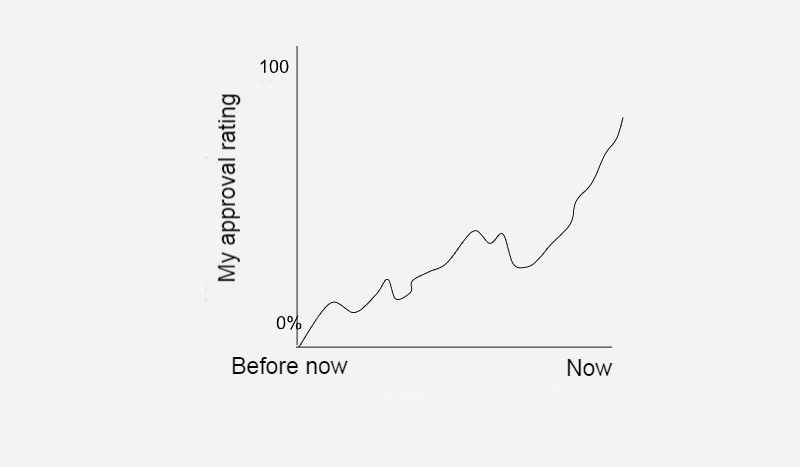

On part of the page, you can draw a graph or chart. This can be added to any of the Three R’s, and can either be rooted in historical fact, or entirely contrived. These can make a note more captivating while supporting your claims.

Example

As you can see in the following chart, people want me to run for president.

Pictures

Drawing a picture is more for creative effect than practical purposes. Where words fail, pictures can do the job.

Example

This will be the new flag of our nation.

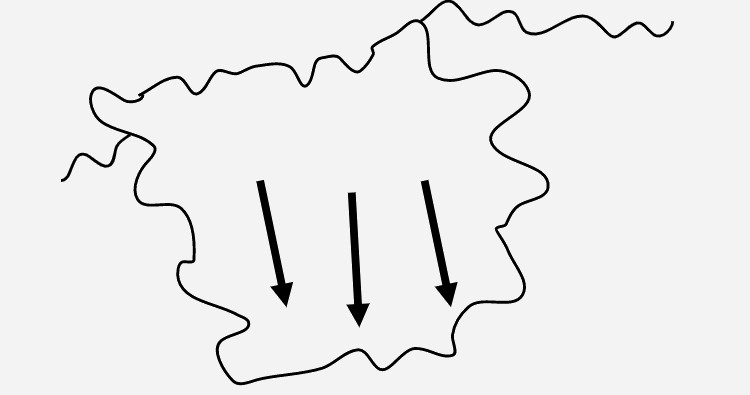

Maps

Maps can be used to describe any geographical strategy. Especially for any military maneuvers, you should recreate accurate maps of the region along with any personnel, supplies, and targets you have in mind. These can also be used to describe territorial claims, environmental plans, trade networks, and more.

Example

“Begin to move all my soldiers to the southern border, in the forests where they can hide.”

Lists

If part of your note is getting too long, turn it into a list. This can be numbered steps or just bullet points. Either way, lists help keep your note organized.

Example

Here is the plan for the coup:

- Organize all our special forces and move them to Washington D.C.

- Once in D.C. the special forces will set up spy equipment around capitol hill.

- On July 4th, break into capitol hill, and hold all government workers hostage.

- Give them our demands.

- Coup them.